Common Stove Repair Issues: Diagnosis and Solutions

Outline and Safety‑First Diagnosis

Before diving into screws and sensors, map the journey. A clear outline keeps your troubleshooting efficient and your kitchen safe. Here’s the plan we’ll follow from symptom to solution:

– Section 1: Safety‑first diagnosis, basic checks, and how to read clues quickly

– Section 2: Electric stove and oven heat problems—elements, switches, fuses, and wiring

– Section 3: Gas burner and ignition issues—spark, flame quality, and regulators

– Section 4: Oven temperature and control faults—sensors, calibration, and airflow

– Section 5: Preventive maintenance, repair‑vs‑replace, and the takeaway you can act on today

Start with safety. Always disconnect power at the breaker for electric models and close the gas shutoff valve for gas units. If you smell a strong gas odor, do not investigate with flames or switches; ventilate, leave the area, and contact your utility or a licensed pro. With hazards addressed, move to the universal quick checks:

– Power supply: For electric ranges, confirm the double‑pole breaker hasn’t half‑tripped; a 240‑volt circuit can lose one leg, leaving lights on but no heat

– Gas supply: Ensure the manual shutoff valve handle is parallel to the pipe for open flow

– Visual inspection: Look for scorched terminals, loose connectors, frayed wires, cracked igniters, or broken elements

– Controls: Verify settings—bake vs. broil, convection vs. conventional, child lock, and any delayed start timers accidentally engaged

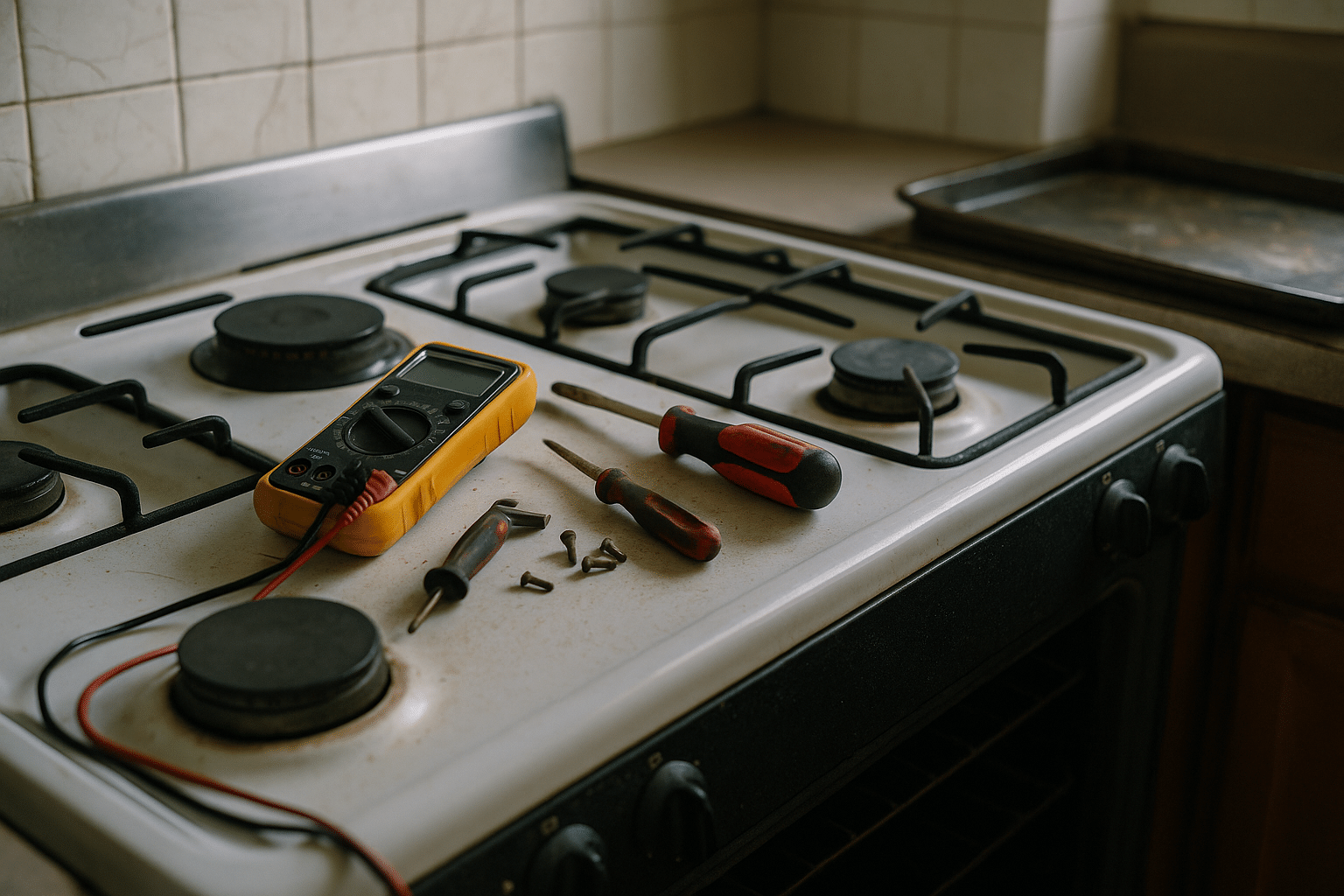

Use your senses like a technician. The rhythmic tick‑tick means a spark module is trying to work; a quiet hiss with no ignition hints at gas flow without spark; glowing but no flame in a gas oven often points to a weak hot‑surface igniter. For electric units, a dead element with visible blisters or breaks is suspicious, while a solid‑looking element may still be electrically open. A simple multimeter transforms guesswork into facts:

– Continuity test: A good surface coil or bake element typically shows continuity; infinite resistance signals failure

– Resistance ranges: Many bake elements read roughly 15–40 ohms depending on wattage; plug‑in coil burners often land around 20–40 ohms

– Temperature sensors (RTD): Common sensors measure near 1000–1100 ohms at room temperature, rising predictably with heat

Think of diagnosis as detective work. Begin with the broadest causes—power or fuel—then close in on specific suspects—elements, igniters, switches, sensors. A methodical approach saves time, avoids part‑swapping, and protects you from risky shortcuts. When in doubt about gas fitting, sealed wiring, or sheet‑metal edges, pause and call a certified technician; knowing your limits is part of smart repair.

Electric Stove and Oven Heating Problems: Elements, Switches, and Wiring

Electric cooking appliances are straightforward in concept: current flows through a resistive element that glows hot. Yet several components can interrupt that simple loop. If a surface burner won’t heat, work from the outside in:

– Confirm the breaker: A partially tripped double‑pole breaker can leave lights and clocks working, but prevent heating

– Test the element: Remove the coil or inspect the radiant element; check for continuity and visible damage

– Examine the receptacle and terminals: Darkened, loose, or melted contacts cause intermittent heating and arcing

– Review the control: Infinite switches for coil tops and surface radiant controls can fail and deliver no power despite a click

For ovens, a common no‑heat or partial‑heat symptom is a failed bake element. The broil element may still function, leading to aggressively top‑browned food and undercooked bottoms. A quick resistance check can confirm a break; many bake elements read between 15–40 ohms. If both bake and broil are out, shift your attention to the terminal block, thermal fuses, and wiring harnesses. A blown thermal fuse—often triggered by runaway heat or blocked ventilation—will cut power until replaced, but it’s vital to address the cause, not only the symptom.

Intermittent heating deserves special attention. Loose connectors at the rear terminal block can heat up under load, scorch insulation, and drop voltage to elements. If you see discoloration or melted plastic, replace the damaged components and ensure screws are torqued snugly. For smooth‑top radiant units, a failed limiter inside the element can produce short cycling and sluggish preheats; these elements are sealed, so replacement is the remedy. If you have dual or triple radiant elements, incorrect wiring after a prior repair can trap you on a single inner ring—double‑check schematics before assuming the part is faulty.

Controls add another layer. Many ranges use an electronic control board to manage oven relays and temperature logic. If an oven remains cold even though elements test good and fuses are intact, listen for relay clicks during a bake command. Silence can indicate a failed board or lack of input from a defective temperature sensor. Typical oven sensors read around 1080 ohms at 70°F and approximately 1650 ohms near 350°F. A sensor reading far outside these ballparks, or a sensor with damaged wiring, will confuse the control and stall preheats. When the display shows error codes, consult the manual to decode them, then verify with a meter rather than guessing. Electrical diagnostics reward patience; one careful hour can prevent days of needless part returns.

Gas Burner and Ignition Troubles: From Click to Flame

Gas stoves offer instant heat, but ignition depends on clean pathways and precise timing. If a top burner clicks without lighting, start at the burner cap and ports. An off‑center cap, debris from a boil‑over, or a film of cooking oil can disrupt the path between spark and gas. Clean the cap and the tiny port next to the igniter, let parts dry fully, and try again. A healthy spark has a crisp snap and a visible arc to the cap or burner head. If the spark is weak or wandering, inspect the porcelain electrode for cracks and ensure the wire is firmly seated and not frayed. Moisture trapped after cleaning is a frequent, invisible culprit—give it a few hours or use gentle airflow to dry.

When none of the burners ignite but you hear clicking, check grounding and power supply. Spark modules need stable power and a good ground to fire reliably. If only one burner fails while others ignite, the spark module likely works and the issue is local—dirty ports, a mispositioned cap, or a damaged electrode. Flame quality tells its own story:

– Steady blue flame with small yellow tips: generally healthy combustion

– Mostly yellow, lazy flames: insufficient air or clogged primary air shutters

– Lifting, noisy flames: excess air or unusual drafts

Ovens introduce different ignition systems. Many use a hot‑surface igniter (glow bar) that must draw enough current to open the gas safety valve. An igniter can glow yet be too weak electrically to open the valve—a classic case of “looks fine, doesn’t work.” In many designs, healthy current draw lands roughly between 2.5 and 3.6 amps; if the igniter glows but there’s no flame, suspect aging. Replace the igniter only with the correct type and avoid touching the element surface; oils can shorten its life. For spark‑ignited ovens, listen for the spark as gas flows; repeated tries without ignition warrant a stop for ventilation and troubleshooting.

Gas flow issues occasionally originate upstream. A half‑closed shutoff valve, kinked flex connector, or faulty regulator can starve burners. On converted appliances, an incorrect orifice for the fuel type (natural gas vs. propane) leads to weak or sooty flames. If you recently moved or remodeled, verify the installation specifics before blaming the burner. Use a mild soap solution to check for bubbles at threaded joints after licensed work, and never apply open flame to “test” for leaks. As with all gas handling, if you encounter persistent odor or hissing, stop, ventilate, and contact a professional immediately; safe caution is not a delay—it’s a plan.

Oven Temperature and Control Issues: Calibration, Sensors, and Airflow

Few frustrations rival a cake that crowns early or a roast that lags past dinner. When temperatures wander, measure before you tweak. Place an oven thermometer in the center and run three cycles at a target temperature, allowing full preheat and recovery between checks. Average the readings; a single snapshot can be misleading due to short cycling or temporary heat layering. Many ovens permit user calibration—often in 5–10°F increments—so if your measured average is consistently off by, say, 20°F, adjust once, then retest.

Modern electronic ovens rely on a resistance temperature detector (RTD) sensor. A healthy RTD generally reads near 1000–1100 ohms at room temperature and climbs in a predictable curve as the oven heats (for example, about 1650 ohms at around 350°F). A sensor significantly out of range, or with intermittent connection at its harness, sends the control on a wild goose chase, leading to short cycling, overshoot, or endless preheat. If your sensor checks out and calibration fails to stabilize temperatures, listen for relay clicks on the control board. Stuck relays or burned contacts can prevent consistent power to elements; conversely, a relay welded closed can cause runaway heat, often tripping a thermal cutoff.

Mechanical thermostats in older gas ovens tell a different tale. A capillary bulb senses heat and communicates through a pressure system to the control valve. If the bulb is dislodged from its clips, insulated by foil, or coated with grease, it reads falsely and mismanages flame. Re‑secure the bulb, clean gently, and confirm that foil or liners are not blocking air paths. Proper airflow is a quiet hero:

– Avoid covering racks or cavity floors with solid foil; it traps heat and confuses sensors

– Verify the convection fan (if present) spins freely and is not obstructed

– Inspect the door gasket; a worn seal leaks heat and lengthens preheats

Door integrity matters more than you might expect. Try the “paper test”: close the door on a strip of paper at several points around the perimeter; noticeable looseness suggests gasket compression or hinge wear. Heat loss at the door can be the invisible reason you add ten extra minutes to every bake. Finally, manage expectations by understanding cycling: Ovens naturally swing above and below a setpoint to maintain average temperature. What feels like a misread can be normal cycling if your thermometer captures a peak or trough. Taking three or more readings and averaging them restores perspective—and your pastry plans.

Preventive Care, Repair‑vs‑Replace, and Your Next Step

Repairs are smoother when maintenance keeps parts clean, cool, and correctly aligned. A monthly routine pays off:

– Wipe burner caps and ports; unclog with a wooden toothpick, not metal that can distort openings

– Keep drip pans and the area under elements free of carbonized spills that insulate heat and stress terminals

– Vacuum crumb channels and around the oven’s lower panel to promote airflow

– Inspect the door gasket annually for cracks or flattening; replace if the paper test fails

– Level the appliance so oil and batter don’t creep to one side, overcooking a corner and undercooking the rest

Treat the control system kindly. Avoid foil overlays that block vents near control panels; trapped heat ages boards and displays. When cleaning, don’t flood knobs or touchpads—moisture can sneak into switches and cause phantom inputs. After a deep clean, give igniters time to dry; residual water is a common source of stubborn clicking and delayed flame.

Deciding between repair and replacement benefits from a simple rule of thumb: if the repair cost approaches half the price of a comparable new unit, and the appliance is well into its service life, consider replacement. Age matters because heating elements, igniters, and gaskets tend to reach end‑of‑life in clusters. However, many failures are surprisingly economical to fix—burned receptacles, weak igniters, worn gaskets, or a single oven sensor can restore performance without a major outlay. Evaluate the whole picture: safety, reliability, energy use, and how the appliance fits your cooking routine.

Conclusion: Home cooks and busy families alike gain confidence by following a structured diagnostic path. Start with safety, confirm power or gas flow, and let simple tests reveal whether an element, igniter, switch, or sensor is at fault. Clean pathways and solid connections prevent many repeat failures, while careful calibration brings consistency back to baking and roasting. When the job crosses into gas plumbing, sealed wiring, or sharp‑edged disassembly, call a qualified technician and consider it part of smart ownership. With a bit of method and maintenance, the familiar tick of ignition and the even warmth of preheat return, and dinner gets its rhythm back.